An original essay, first published in A Taste of Scandal, a series sampler

I'm often asked where I get my ideas. It's a popular question to ask authors, especially authors who write books about things they couldn't possibly have experienced in real life, such as long-ago eras or magical fantasies. I think there's a feeling that authors must be different, more creative (or strangely imaginative) than other people for us to conjure up vampires and boy wizards and time-traveling nurses. The truth, though, is that ideas are all around us, like dandelion seeds on the breeze. What makes authors different is our willingness to pluck one of those seeds out of the air, turn it around and admire it, and then set about making it grow.

I'm often asked where I get my ideas. It's a popular question to ask authors, especially authors who write books about things they couldn't possibly have experienced in real life, such as long-ago eras or magical fantasies. I think there's a feeling that authors must be different, more creative (or strangely imaginative) than other people for us to conjure up vampires and boy wizards and time-traveling nurses. The truth, though, is that ideas are all around us, like dandelion seeds on the breeze. What makes authors different is our willingness to pluck one of those seeds out of the air, turn it around and admire it, and then set about making it grow.

For instance, a couple of years ago a particular book started popping up on the bestseller lists. I saw ten different people reading it during my vacation at the beach. Saturday Night Live aired sketches highlighting its naughtiness. The book, of course, was 50 Shades of Grey. I didn't quite realize the reach of its appeal, though, until I discovered my teenaged daughter had bought it on her e-reader. When I asked about it—this was not her usual sort of book purchase—she defensively replied, "Well, everyone is talking about it, and I just wanted to see what the fuss was!"

So here was the seed of an idea: a book so intriguing everyone wants to get their hands on it, yet naughty enough that one might not just walk into the nearest bookseller and buy it.

So here was the seed of an idea: a book so intriguing everyone wants to get their hands on it, yet naughty enough that one might not just walk into the nearest bookseller and buy it.

Anyone who's read The Canterbury Tales or the Decameron knows that explicit stories are nothing new. Long before 50 Shades became a phenomenon, people were reading sexy books. In the fifteenth and sixteenth century, Italy was the primary source, from illustrated erotic sonnets to 'histories' of prostitutes' lives. In the seventeenth century French writers gained popularity, although their works presented sex as generally sinful or corruptive, where the Italians had taken the approach that sexual pleasure was irresistible and fundamentally good. And the English imported from both countries before seizing the genre and extending its boundaries into even more taboo and explicit expressions.

By the 1700s, the street corners and taverns of London offered all manner of erotic writings and drawings. One could hear risque ballads recited at the tavern, or buy a twopenny illustrated broadsheet at a street fair. Coffee houses, then an emerging social center, sold books and prints, which were no doubt read and enjoyed right there over a hot drink. Translated foreign erotica, especially French, still did a roaring trade as well, often edited to appeal to particularly English preferences. Anything French was perceived as racy, so English authors would use French words to add an extra level of titillation to their writing.

By the 1700s, the street corners and taverns of London offered all manner of erotic writings and drawings. One could hear risque ballads recited at the tavern, or buy a twopenny illustrated broadsheet at a street fair. Coffee houses, then an emerging social center, sold books and prints, which were no doubt read and enjoyed right there over a hot drink. Translated foreign erotica, especially French, still did a roaring trade as well, often edited to appeal to particularly English preferences. Anything French was perceived as racy, so English authors would use French words to add an extra level of titillation to their writing.

Somewhat surprisingly, since most of it was written by men, a lot of historical erotica is told from a woman's point of view, or with a strong female focus. The School of Venus from 1680 is written as a conversation between two young women, with the older one instructing the younger one on every point of sex and pleasure. Titles like The Accomplished Whore and The Crafty Whore reveal another popular figure: the prostitute, who presumably was appealing for being a woman who engaged in frequent sex with multiple partners. In fact, one of the most famous erotic works in history was originally published as Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure, with 'woman of pleasure' being a euphemism for prostitute. It later became better known by the name of its protagonist and narrator, Fanny Hill (click to read at Google Books).

Perhaps for this reason, women enjoyed these books and ballads, and sent their chambermaids to fetch the latest publications from the Covent Garden booksellers. Authors certainly knew it; more than one naughty book begins with sly remarks addressed 'to the ladies.' Popular ladies' magazines of the time printed scandalous trial reports (trials for adultery being particularly salacious) and ribald poems. Some women even kept libraries of erotic books, including sex guides and pornographic drawings.

Perhaps for this reason, women enjoyed these books and ballads, and sent their chambermaids to fetch the latest publications from the Covent Garden booksellers. Authors certainly knew it; more than one naughty book begins with sly remarks addressed 'to the ladies.' Popular ladies' magazines of the time printed scandalous trial reports (trials for adultery being particularly salacious) and ribald poems. Some women even kept libraries of erotic books, including sex guides and pornographic drawings.

Just because books were readily available didn't mean all of society approved of them. More than one author and publisher of "obscene" works faced prosecution and jail, including John Cleland, the author of Fanny Hill. Cleland was already in prison for debt when Fanny Hill was first published. Fanny's success may have helped him get out of jail by allowing him to pay his debts, but within a year he was under arrest again along with his publisher. This didn't stop the book from selling like hotcakes—illicitly, of course. One magazine reported that Fanny Hill earned its publisher ten thousand pounds, an absolute fortune if true.

Fanny's story is told through a series of letters to an anonymous reader. As a young woman Fanny leaves her ordinary, honest life and goes to London to seek her fortune. She's pretty, naive, and broke, and promptly gets swept up by a brothel. Fanny makes the euphemism true: she finds a great deal of pleasure in her new vocation. Unfettered by a husband, parents, or inhibitions, she enjoys her life and her sexual adventures with men and women, every moment of which are described in extravagant—though not vulgar—detail. After several years and many partners, Fanny finds herself in possession of a fortune and reunites with her first lover, Charles, who promptly marries her. After all the licentious acts, Fanny still ends up with her own happily-ever-after, making her something of a forerunner of the erotic romances of today.

Fanny's story is told through a series of letters to an anonymous reader. As a young woman Fanny leaves her ordinary, honest life and goes to London to seek her fortune. She's pretty, naive, and broke, and promptly gets swept up by a brothel. Fanny makes the euphemism true: she finds a great deal of pleasure in her new vocation. Unfettered by a husband, parents, or inhibitions, she enjoys her life and her sexual adventures with men and women, every moment of which are described in extravagant—though not vulgar—detail. After several years and many partners, Fanny finds herself in possession of a fortune and reunites with her first lover, Charles, who promptly marries her. After all the licentious acts, Fanny still ends up with her own happily-ever-after, making her something of a forerunner of the erotic romances of today.

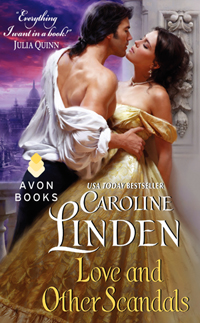

I read Fanny Hill while working on Love and Other Scandals. My heroine, Joan, is tall and unfashionable and beginning to fear she'll never get married even though she longs to find someone who will find her attractive and desirable…although she isn't really sure what that would mean. During the English Regency, sexual education for girls was pretty limited, and I pictured Joan as a young woman desperately curious about sex but worried that she'd never find out firsthand. I could also imagined her sneaking around to get her hands on a notorious naughty story that other women whispered about behind their fans. And from that came my own version of Fanny Hill, called 50 Ways to Sin, an erotic serial which fascinates Joan and her friends.

Like Fanny Hill, 50 Ways to Sin is a series of letters detailing the erotic adventures of a bold and daring woman. Unlike Fanny, my Lady Constance isn't a prostitute but a widowed lady with money of her own. She takes lovers because she chooses to, but only for one night; a lady must have some discretion, after all. Her partners all bear striking resemblances to well-known men in society, much the way period gossip columns would reveal people's affairs in thinly veiled magazine tales. Her stories scandalize and mesmerize London, the most talked-about and taboo subject in town. And like Fanny, I planned for Lady Constance to have a story arc of her own.

Like Fanny Hill, 50 Ways to Sin is a series of letters detailing the erotic adventures of a bold and daring woman. Unlike Fanny, my Lady Constance isn't a prostitute but a widowed lady with money of her own. She takes lovers because she chooses to, but only for one night; a lady must have some discretion, after all. Her partners all bear striking resemblances to well-known men in society, much the way period gossip columns would reveal people's affairs in thinly veiled magazine tales. Her stories scandalize and mesmerize London, the most talked-about and taboo subject in town. And like Fanny, I planned for Lady Constance to have a story arc of her own.

These stories have underpinned my Scandalous series of books, providing some sex ed to my well-bred 19th century heroines. In historical romance the heroines are often less sexually experienced and knowledgeable than modern young women. I've always disliked making the heroine far more ignorant than the hero. Erotica helps level that playing field a bit by giving frank depictions of the ways people can find pleasure together, knowledge that would have been unavailable to—though desperately desired by—young women of the 1820s.

The history of erotica is fascinating, and eye-opening. Anyone who thinks people three hundred years ago were more prudish or modest than today…is wrong.

The history of erotica is fascinating, and eye-opening. Anyone who thinks people three hundred years ago were more prudish or modest than today…is wrong.