“Have they gone?”

“Have they gone?”

Mr. Edwards closed the door of the duchess’s private sitting room behind him. “Yes, Your Grace. Maximilan and his wife departed an hour ago.”

The duchess nodded and sipped her tea. She was exceedingly fond of the new service already. Surreptitiously she tilted her cup to catch the light, marveling at the depth of the ruby red glaze. And how astonishing that Mrs. St. James had created it. A woman, working in a factory! It was extraordinary. “He’s turned out better than I expected.”

“It is a very gratifying surprise to me as well, ma’am.”

The duchess sniffed. She had suspected Maximilian would squander his five hundred pounds in an orgy of excess. Gamblers could never resist the lure of risking it all; less often did they contemplate losing it all. His amused little smile as she outlined her plan in the spring had irked her, and convinced her he was neither serious nor conscientious, unwilling—or unable—to grasp the enormity of the Carlyle inheritance, even when it was explained to him in detail. Visions of him gambling away the entire estate upon Johnny’s death had tormented her. She had predicted he would appeal for more funds before the six-month was up.

Mr. Edwards had been less sure; he thought Maximilian was too used to surviving by his wits, and far too proud to crawl back asking for more. He thought there was more to the man—a quiet but fierce intelligence, and seething, frustrated ambition.

Well. That was abundantly clear now. Maximilian had defied all her expectations and turned up on time, prosperous and respectable with a clear-eyed, clever wife at his side. She did so hate it when Mr. Edwards was right and she was wrong.

“You told him there has been no word from the captain?”

“Yes, ma’am.”

“Hmm.” She took another sip of tea. “What did he say to that?”

The solicitor paused, always a bad sign. “He was astonished. He had persuaded himself he would never inherit, and considered his involvement with the Castle concluded.”

“What?” burst out Her Grace. “I knew he was not taking this matter seriously!”

Edwards held up one hand. “I persuaded him not to be so hasty.”

“Hmph. Once a rogue, always a rogue,” she muttered.

“He has undertaken a prominent role in the Perusia factories,” was her solicitor’s mild rebuttal. “Over two hundred men under his oversight, with showrooms and warehouses in London and Liverpool, and plans to expand. He has made something of himself.”

“That is nothing to Carlyle,” she charged.

“No,” conceded her solicitor, “but it is… progress.” He sounded impressed. And Edwards would know. She had told him to keep an eye on Maximilian, and see what he got up to.

More fool her. She ought to have set him to watching the captain, the far more satisfactory heir who had nonetheless let her down.

More fool her. She ought to have set him to watching the captain, the far more satisfactory heir who had nonetheless let her down.

The cruelest part was how promising the captain had been. He had remained at the Castle for almost two months, listening to everything she said and doing everything she asked. The duchess had smiled complacently as he rode off to tie up his life in Scotland.

“See, Mr. Edwards?” she had said in triumph. “We do not need any other heirs. This one will be more than adequate.”

The captain, alas, had vanished into the wilds of Scotland without a trace. It was not mere happy surprise that Mr. St. James had turned out so well, but a vast relief.

She did so hate to be wrong.

“I told him I would continue paying his income,” Mr. Edwards went on, “and that he should not presume he has no hope of Carlyle. He understood at once.”

Irritably she waved one hand. “Yes, yes, yes, I take your point. He is not the worthless wastrel I thought him, nor a fool. He may even be capable!” That last wrung a faint smile from Mr. Edwards. “In turn, you must admit I was correct, and marriage has improved him considerably,” she charged. “I did like his wife.”

Mr. Edwards bowed. “I never deny your insight, ma’am.”

“The right wife can settle even the wildest rogue.” She sighed. “But still—keep a close eye on Mr. St. James yet. If the captain can go missing on so trifling an errand as visiting his family, who knows what might befall Mr. St. James? A fall from his horse, a fever caught in the rain, and we shall be back where we began, with no heir at all.” As much as it broke her heart to admit it, her son was not in good health. A mother was not supposed to bury all of her children.

“One devoutly hopes not, madam.”

“Of course one hopes not!” she replied irritably. “I do not have time or patience for hope, sir! I suppose there is still no word from Edinburgh?” She didn’t know why she kept asking. At this point, Edwards would probably rouse her from her bed after midnight if he received word from Edinburgh.

“No, Your Grace.”

“No, Your Grace.”

She sighed, hating what she had to say next. “We cannot afford to lose another heir. I suppose you’ve discovered nothing about… the other one.”

He waited, brows lifted, forcing her to say it.

“The Frenchman,” she said through gritted teeth. As little as she liked to think of a Frenchman inheriting, it must be faced; she could no longer put it off.

“No, ma’am. I have been looking—”

“Look harder, Mr. Edwards,” she snapped, even though she had scorned all his previous efforts at finding Lord Thomas St. James.

Initially she had opposed it on principle. Neither Thomas nor any heir of his had never made the slightest effort to contact the Castle. How could he, or they, possibly care for it? For all their distance from the Castle, the captain had never hidden his connection to Carlyle, and Maximilian had even flaunted his on occasion. Surely, she had argued, it was more important to focus on preparing the heirs they had at hand.

It vexed her to no end that a French heir, if one existed, would supersede both of them. Heaven alone could imagine what she would have to do to make a Frenchman worthy of Carlyle.

She indulged in a moment’s resentment of Anne-Louise, the duchess who had fled, the Frenchwoman who would have been her mother-in-law. Sophia could not blame Anne-Louise for running away; the third duke had been a cold and imperious tyrant. But taking Thomas with her… That was unforgivable. It obliged the duchess to search for him now, a task which would be difficult enough thanks to the eighty years that had elapsed since their flight, but now every month brought distressing news of rampant turmoil in France. Tracing Thomas might prove impossible.

And worse, merely searching engendered risk. If he had disappeared completely, that was one thing—and wouldn’t sadden her at all. What frayed her nerves was the chance that there would be just enough evidence of Thomas or his children to cause the Crown to deny the captain’s ascension to the title. That could throw Carlyle into abeyance, a dukedom without a duke.

She must protect Carlyle. She had little else left.

“I will redouble my efforts, Your Grace.” Edwards hesitated a moment. “On the other pressing matter…”

Oh Lord. She rolled her eyes, bracing herself for a continuation of their long-running disagreement.

Oh Lord. She rolled her eyes, bracing herself for a continuation of their long-running disagreement.

“I have interviewed several candidates for the position of estate manager—”

She waved her hands and scowled at him. “Oh, go to, Mr. Edwards! Enough!” She was sick unto death of hearing about estate managers. Would that dear old Grimes had recovered, but alas; he was unquestionably indisposed. She had finally agreed to his pension.

“No, no, ma’am, I believe I have found someone who will satisfy your every requirement,” he said. “I would like permission to engage him.”

She eyed him suspiciously. “Who is he?”

“His name is Montclair, ma’am—”

“French!” She lurched in her chair.

“No, no,” said Edwards quickly. “He is from the provinces.”

“American!” she exclaimed in greater horror.

“Canada,” said Edwards at almost the exact moment. “He is a sensible man, intelligent and capable.”

“Hmph. Is he married?”

Mr. Edwards cleared his throat. “I do not believe so, ma’am. He is a bit young—”

She knew it. Edwards had been scheming to install a brash young man who would upend the system she had painstakingly preserved for thirty years, and now he’d found a French provincial one, as if he wanted to spite her. “Mr. Edwards, I require a man of experience! None of these innovative young scoundrels who will want to kick over the traces for sport!”

“—Which I believe will enable you to mold him precisely into the steward you wish him to be,” interjected the solicitor smoothly. “An older man would be set in his ways and unwilling to adapt. Someone other than an Englishman will not have the usual prejudices and presumptions. In addition, a younger man will be able to direct Carlyle for years to come, ensuring continuity no matter who the heir presumptive is. I was highly impressed by him, Your Grace.”

The duchess snapped her mouth shut and glared at her attorney, standing there with a subtle air of satisfaction. He knew when he had outflanked her, the old fox. Oh, she did despise that.

“Very well,” she said at last, grudgingly. “If you vouchsafe that he is suitable, engage him for a six-month. I shall reserve judgement until then,” she added, lest he think he had won on all counts.

“Thank you, Your Grace.” Edwards bowed. “I will do so at once.”

Philippa Kirkpatrick paused outside the duchess’s sitting room. Through the door she could hear raised voices: the duchess’s, sharp and nettled, and Mr. Edwards’s, lower and calmer. A faint smile touched her lips. What were they arguing about now, she wondered fondly.

Philippa Kirkpatrick paused outside the duchess’s sitting room. Through the door she could hear raised voices: the duchess’s, sharp and nettled, and Mr. Edwards’s, lower and calmer. A faint smile touched her lips. What were they arguing about now, she wondered fondly.

At the first moment of silence, she tapped on the wooden panel and let herself in. The duchess sat at her table, her mouth pursed up in pique. Mr. Edwards stood with his hands clasped behind his back, his expression serene but somehow satisfied. Oh dear; he’d won again, which would put the duchess into a despondent mood. She’d grown anxious about her own judgment lately, fretting over any little mistake she made or point she overlooked. She lamented that she was growing old and batty.

Philippa knew it was actually anxiety over the duke’s health and the still-unsettled succession. The duchess’s mind was still sharp and agile.

Unfortunately, her mission now would not ease that fear. “Your pardon, madam, but His Grace is asking for you. Heywood sent me to tell you immediately.”

With surprising speed and agility, the duchess was out of her seat and across the room. “That will be all, Mr. Edwards,” she called as she hurried off to see her son.

Mr. Edwards sighed, visibly deflating. Philippa gave him a sympathetic look. He was a good man, trying to do a difficult job.

Now he turned toward her. “How fares His Grace, Miss Kirkpatrick?”

She lowered her gaze. “Not well, sir.” The duke had developed a dry, raspy cough that wouldn’t stop. “The doctor is concerned.”

The solicitor nodded gravely. “And Her Grace?”

Philippa bit her lip. He was not asking her to spy on the duchess; he never had, and she never would. The duchess knew he asked Philippa’s opinion, and she always encouraged a reply. Put that wily fox’s mind at ease that we’re not withering away of incompetence here, she always said. Philippa rather thought the duchess appreciated the lawyer more than she ever said, even though they sparred like two birds over a worm.

But in the last several months, something had shifted. Philippa the loyal companion and Edwards the put-upon solicitor had tacitly formed an unspoken pact to support and protect the duchess. She was the strongest woman Philippa had ever met, and yet she had suffered so much heartbreak. Losing her youngest son this spring had been a terrible blow; not only had Lord Stephen been the apple of the duchess’s eye, his death stripped away her last remaining hope of grandchildren and an heir to the estate.

“Of course she is alarmed, sir,” she replied to the solicitor’s question. “But His Grace has long suffered in the summer, with difficulty breathing, and has always rallied before. Mrs. Potter has been brewing her poultices and tonics that usually make him better.”

“Excellent,” murmured Mr. Edwards. Like Philippa, he had a high regard for the housekeeper’s poultices and tonics. He regarded her thoughtfully for a few minutes. “What did you think of Mr. and Mrs. St. James?”

She glanced at him warily. It was unusual for him to ask her about anything except the family. Although, of course, the recent visitors must now be considered family. “They are very amiable.”

She glanced at him warily. It was unusual for him to ask her about anything except the family. Although, of course, the recent visitors must now be considered family. “They are very amiable.”

“Hmm. Yes. And do you feel,” the solicitor asked, obviously choosing each word with care, “they could step ably into the roles of duke and duchess, in the event Captain St. James has gone missing forever?”

She started. What did he mean by that? “Yes… but surely the captain will return.”

“Of course. But if perchance he does not…?”

Philippa’s heart seized. The duchess had fretted over the captain’s prolonged absence, but without genuine alarm. She’d thought his delay was an irritation, not a crisis.

Mr. Edwards must know something—something he had kept from the duchess, or something so alarming the duchess hadn’t wanted to speak of it. “What do you mean, sir? Do you fear he won’t?”

“I sincerely hope he does return,” he replied at once. “And soon.”

“So do we all,” she said a bit sharply. “But do you expect him to return?”

Captain St. James had been a very obliging guest. The duchess had pronounced herself cautiously optimistic after his lengthy visit; a far sight better than I expected, she’d said. The captain had assured everyone that he would be back in two or three months, after concluding his military obligation and seeing his mother and sisters. He had asked Mr. Edwards to locate a suitable property near the Castle for him, large enough for his family. The duchess had begun making a list of suitable young ladies to introduce to him.

“God willing, Miss Kirkpatrick,” Edwards said with a forced smile. “But I have learned not to take anything for granted.”

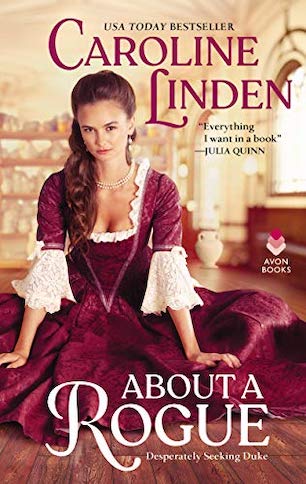

No; of course not. The St. James family had learned that the hard way. Philippa looked away and sank onto the sofa. “To answer your questions about Mr. and Mrs. St. James… this life would be quite alien to them both. Still, I believe Mr. St. James would do what he must, though Mrs. St. James would vastly prefer that it not happen. She is so very fond of her family, sir, and she would not want to leave them, to say nothing of the factory. Whenever she spoke about her work, she became animated in a different way.” She picked up a teacup from the tray. It was a simple, elegant shape, the white body banded by brilliant scarlet, which shone like liquid rubies. “She created this red glaze. Extraordinary, is it not?”

“It is.”

Philippa studied the cup. Bianca St. James had been surprised, but very happy, to explain how she’d spent months tinkering with the ingredients to achieve it. Her enthusiasm had been infectious, leaving Philippa to lie awake that night wondering at the other woman’s perseverance and intelligence. When had she ever dedicated herself to such a pursuit—and one that was not merely a passing achievement, like a lovely flower arrangement, but something that would last and bring pleasure to people decades from now?

“It must be enormously gratifying to create a thing of such beauty,” she said softly, tilting the cup to see the golden rim gleam. “I believe she finds her work very rewarding.”

“Yes.” Mr. Edwards frowned.

Philippa knew what troubled him; formulating glazes was not a duchess’s milieu, and Mrs. St. James’s determination to continue doing so would affect Carlyle, if the dukedom fell to her husband.

Carlyle, Carlyle, Carlyle. Always Carlyle. Nothing else mattered. Either the captain would return, having upended his and his family’s lives to serve Carlyle, or Maximilian and Bianca would have to do so. She had to bite back a hasty exclamation at the unfairness of it.

Her chest felt tight, riven with discontent. Carlyle had been so good to Philippa; why did she envy Bianca St. James so much? Why did her description of long hours tinkering with chemical compounds sound so intriguing? Why did her tales of the Tate family—from good-hearted Cathy to quick-tempered Samuel to tart-tongued Aunt Frances—stir such a longing in Philippa’s breast? Why did descriptions of Poplar House—very small and modest, nothing to the Castle, Bianca had rushed to assure her—exert such a pull on her imagination?

She did not need to look around the room to know it was the epitome of luxury and elegance, with no expense spared, like everything at Carlyle. After her parents’ deaths, the duchess had taken her in as a companion, and been kind and generous, even loving—like the grandmother Philippa had never had. She had given Philippa a home, a purpose, every material comfort. Philippa had learned to ride a pony in the courtyard, danced the minuet in the cavernous ballroom, had her lessons in painting and French in the elegant saloons and on the expansive lawns. Here, Philippa was needed and loved.

But that would not last forever. She set down the cup with a clink.

When she raised her head, her gaze landed on the large portrait hanging opposite her. It was the duchess’s favorite, taking up most of the wall in her private sitting room. It had been painted some forty years earlier, of Her Grace as a vibrant, handsome woman in her late thirties, surrounded by her children. Leaning against her chair with an amused expression was John, the current duke, a tall slender young man with piercing gray eyes. Next to him, arm thrown affectionately around his elder brother’s shoulders, stood William, broader and almost as tall, a confident, even roguish air in his faint smile. Arms laden with flowers held out to her mother was young Jessica, radiant with pink-cheeked exuberance. In Her Grace’s lap, his plump little hand clutching her necklace, sat cherubic Stephen, still in baby dress. All five shone with vitality and joy and careless confidence in a glorious future.

Philippa’s eyes went, as they always did, to Jessica. She adored this portrait of her stepmother as a girl of ten. Jessica had told her, laughing, how they had all despised sitting for this portrait. John and William had cracked jokes and played pranks on each other until the duchess scolded them. Stephen had fussed and cried until he was red in the face, and then got sick all over his mother’s gown. Jessica remembered how very heavy her armful of flowers had been, and how the painter had snapped at her if she didn’t hold them just so.

Philippa’s eyes went, as they always did, to Jessica. She adored this portrait of her stepmother as a girl of ten. Jessica had told her, laughing, how they had all despised sitting for this portrait. John and William had cracked jokes and played pranks on each other until the duchess scolded them. Stephen had fussed and cried until he was red in the face, and then got sick all over his mother’s gown. Jessica remembered how very heavy her armful of flowers had been, and how the painter had snapped at her if she didn’t hold them just so.

“It’s a good thing it pleases Mama so much,” she had whispered to young Philippa, holding her close. “We all thought it a very miserable experience!”

Philippa sighed bittersweetly at that memory. The duchess did love the portrait, yet it must also remind her, every day, of all she had lost.

She started to look away, but her gaze caught on a different face this time—William’s, the second oldest. Like her papa, he had gone into the army. Like her papa, he had been sent overseas and killed in battle half a world away. The military was a dangerous career.

“What do you think has happened to him?” she asked softly. “Captain St. James.”

After a hesitation, the solicitor came around the table and paused, waiting for Philippa’s quick nod of invitation before he sat down. “I did not mean to alarm you, Miss Kirkpatrick. I have no reason to believe the worst.”

“Then why has he not returned, or at least replied to your letters?”

Mr. Edwards made an equivocal motion with one hand. “Perhaps his family situation was more complicated than expected. I understand he last saw his mother and sisters over a year ago. Much may have gone awry in that time.”

“But would he not write to ask for more time to handle the matter, in that case?”

The solicitor hesitated again. “I would have preferred it, but without knowing…” He shrugged. “I suspect he does not fully comprehend the changes in store for him and his family. I don’t wish to judge him too harshly.”

Philippa nodded, thinking that she was not so lenient. The captain ought to have understood, after his time here, how much the duchess was counting on him. He had better have a good reason for disappearing, she thought impatiently, and then instantly felt remorseful; what would a good reason be? Death? Injury? Family disaster? She didn’t wish any of those on him

“How likely do you think it that there is another heir?” she asked abruptly.

Mr. Edwards started, his eyes narrowing.

“Her Grace mentioned the possibility of another.” Philippa smoothed her skirts. “The succession has been weighing on her, particularly in the captain’s absence.”

“Her Grace mentioned the possibility of another.” Philippa smoothed her skirts. “The succession has been weighing on her, particularly in the captain’s absence.”

The captain’s absence was troubling because of the duke’s declining health, which was a closely guarded secret. If the true nature of His Grace’s infirmity were known, there would be questions—inquiries—scandal. Her Grace was fiercely determined that no one would charge her son with incapacity or attempt to wrest control of the estate from her hands.

When the captain had stopped answering letters from Carlyle, the duchess had grown increasingly upset until she confided, in a burst of irritation, that there might be another heir, a Frenchman, even nearer than the captain—and that if the captain couldn’t be counted upon, they would have to search out this missing Frenchman, which Her Grace was very loath to do.

“There is a chance, yes,” said the solicitor after a long moment.

Philippa let out her breath, suddenly trembling. Another heir. The captain had been polite and gentlemanly. Maximilian was a bit more guarded, but Bianca St. James had felt almost like a sister, by the time she and her husband left the Castle.

Philippa had persuaded herself that either Maximilian or the captain would make an able and admirable duke, no matter which inherited the dukedom. But to think of another, unknown person, inheriting everything… That was what had distressed the duchess so terribly, she realized. The captain had impressed Her Grace, and so had Maximilian, against all odds. She had made peace with one of them inheriting, and now it might be all for naught.

“Mrs. St. James would be relieved to hear it, at least,” she said at last, striving for poise and evenness. She glanced at the solicitor. “But… you’ve not found him yet, have you? The other heir.”

Mr Edwards sighed. “Such a person, or persons, may not even exist. Until we search, and search thoroughly, we will not know. And as you said, the captain’s disappearance makes it critical.”

Philippa looked at her hands in her lap. “Of course. I understand. Thank you, Mr. Edwards,” she murmured.

He gave her a smile clearly meant to be reassuring. “Rest easy, Miss Kirkpatrick. I still have faith everything will end well.”

She made herself smile and nod, and hoped he was right. The solicitor left the room, and she was alone.

Once more her gaze drifted to the portrait. The duchess sat regally at the center of her family, proud and lovely, a faint smile on her lips, no doubt imagining the brilliant futures her children would have. She had always been a loving and devoted mother. What would she do when only Carlyle, the estate, was left, after Carlyle, the man, had slipped away?

Once more her gaze drifted to the portrait. The duchess sat regally at the center of her family, proud and lovely, a faint smile on her lips, no doubt imagining the brilliant futures her children would have. She had always been a loving and devoted mother. What would she do when only Carlyle, the estate, was left, after Carlyle, the man, had slipped away?

She will have me, thought Philippa fervently. More than once the duchess had suggested a young woman must want a husband and a home of her own; she had offered to send Philippa to London for a proper season. But the Castle was the only home Philippa knew, and the duchess was like a grandmother to her. Philippa could not imagine leaving her, certainly not when the duke was so ill and the captain was still missing.

So she got up and went to find Her Grace, determined to provide any comfort she could, come what may.